|

SUMMARY:

Look I’ll admit it. Given a choice, I’d prefer to avoid math and data. I didn’t get into marketing because I was passionate about spreadsheets. I got into marketing because I love to write…create…make things – hence the name of our podcast. At the same time, after a career in marketing I am a skeptic. I want evidence. Which…often comes in the form of data. And that is the challenge of marketing today folks – how can those with a creative heart still tap into the evidence that data provides? So, I was excited to see the pedigree of the guest in our latest podcast episode. The guest application was from a man of the theater, and yet, his application was filled with words like “data-driven” and “deep statistical analysis of large data sets.” Listen to the latest episode of the How I Made It In Marketing podcast to hear lesson-filled stories from Michael Diamond, Academic Director and Clinical Assistant Professor in Integrated Marketing and Communications, NYU School of Professional Studies. |

This article was published in the MarketingSherpa email newsletter.

“Trust yourself.” That is a key lesson shared by our latest guest, an academic leader. And really, that is the goal of education, right? To build your capacity, so you can trust yourself to effectively execute.

We also believe in the importance of capacity building for entrepreneurs and marketing professionals. For example, we provide free marketing thought tools – simplified frameworks to help spark your next great marketing campaign. We call them “thought tools” because they help spark your ideas and insights, so you can trust yourself instead of trusting some tools’ secret AI to magically provide the answer.

“Trust yourself” is just one of the lessons shared by Michael Diamond, Academic Director and Clinical Assistant Professor in the Integrated Marketing and Communications Department, New York University School of Professional Studies, in our latest podcast episode. Diamond supports over 1,000 graduate students and more than 200 faculty members at NYU.

You can listen using the embedded player below or click through to your preferred audio streaming service.

Listen on Spotify | Listen on Podcast Addict | Listen in Amazon Music

Some lessons from Diamond that emerged from our discussion:

Build capabilities that endure, and not just quick fixes to near-term problems.

As Head of Strategy and Insights at Time Warner Cable, Diamond partnered with Steven Goldbach to identify consumers that had the highest propensity to bundle services. They conducted deep statistical analysis of large data sets across 30 million households. The goal was to provide actionable insights to help everyone at the company – from customer service reps learning how to upsell to senior leaders considering mergers and acquisitions.

Diamond discussed his idea of data poetry – bringing out the beauty in data – by quoting Alexander Pope, “What oft was thought, but ne'er so well express'd.”

Tackle problems with integrity, self-reflection, and some humor.

As acting CMO of Time Warner Cable, Diamond led the team that built out a series of ads that faced up to problems honestly and specifically and did so with a tone of self-effacing good humor. He quoted Cicero’s maxim, “The effect is in the affect,” to explain the importance of leaving customers with the right feeling.

Trust yourself and your instincts, especially when you feel passionate about something.

Diamond teamed with Artie Bulgrin and others to rebrand the CTAM Research Conference to CTAM Insights Conference and brought in new types of attendees and speakers – like Dawn Hudson. CTAM is the Cable and Telecommunications Association for Marketing.

Diamond discussed driving change in an organization, and quoted Arthur Schopenhauer, “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.”

Stories (with lessons) about the people he made it with

Diamond also shared lessons he learned from the people he collaborated with:

Don Logan, co-COO, Time Warner: Speak truth to power.

Logan was the esteemed and very successful former Chairman and CEO of Time Inc., under who's stewardship the company had launched several new brands, (for example, Real Simple), made significant international acquisitions, and ventured into the early days of the internet. He came over to be co-CEO of a of Time Warner Inc, and his portfolio was to run all of the subscription-based businesses, which included AOL, Time Inc. magazine and the cable company. And then Jeff Bewkes at the time was the other co-CEO, and he ran the studios, the music labels, and the networks (like HBO).

When Diamond asked Logan what role he could play as Chief of Staff, Logan said – give it to him straight, speak truth to power.

Victoria Stapf, Executive Assistant, Time Warner: Trust yourself.

When Diamond got a big new position, he struggled at first. One day Stapf brought in a small rock engraved with the words “Trust Yourself.” Now, Diamond works with Antonio Lucio to teach marketers about the importance of trust and purpose for companies’ relationship with their customers.

Janet Harris, Director of Development, Manhattan Theatre Club: “We hired you because you are smart, you have our support, and we expect you can figure it out.”

Harris gave Diamond this advice when Diamond had self-doubt in his first real job at this renowned institution run by Barry Grove and Lynne Meadow.

Judith Harrison, EVP Global Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, Weber Shandwick: “It’s not just the how and what of marketing and PR, but often ‘who’ is in the room.”:

In Diamond’s current role at NYU, Harrison carefully reminded him that access is an important aspect of DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion).

The MarketingExperiments Quarterly Research Journal

Executive Master's in Marketing and Strategic Communications

Franchising and Marketing: In a world of chicken dinners, be a lobster dinner (Podcast Episode #14)

Marketing Wisdom: In the end, it’s all about…

This podcast is not about marketing – it is about the marketer. It draws its inspiration from the Flint McGlaughlin quote, “The key to transformative marketing is a transformed marketer” from the Become a Marketer-Philosopher: Create and optimize high-converting webpages free digital marketing course.

Not ready for a listen just yet? Interested in searching the content? No problem. Below is a rough transcript of our conversation.

Daniel Burstein: Look, I'll admit it. Given a choice, I would prefer to avoid math and data. I didn't get into marketing because I was passionate about spreadsheets. I got into marketing because I loved to write and create, to make things. Hence the name of this podcast, right. At the same time, after a career in marketing. I'm a skeptic. I want evidence which often comes in the form of data. And that is a challenge of marketing today, folks. For you. For me. How can those with a creative heart still tap into the evidence that data provides?

So I was excited to see the pedigree of our next guest in his application to be a guest on how I made it in marketing. He was a man of the theater, and yet his application was filled with words like data driven and deep statistical analysis of larger data sets. So I can't wait to see what we can learn from our next guest's stories. Joining me now is Michael Dimond, Academic Director and Clinical Associate Professor in Integrated Marketing and Communications at the NYU School of Professional Studies. Thanks for joining us, Michael.

Michael Diamond: Daniel, it's absolute pleasure to be with you. Thank you so much.

Daniel Burstein: It's going to be a lot of fun. So let's first look at your background real quick at a high level so that people know who they're hearing. A former Senior Vice President and Acting Chief Marketing Officer for Time Warner Cable, where you led marketing for its $19 billion residential business. Early in your career you were a strategy consultant for Booz Allen Hamilton. And right now you are a lecturer at the Yale School of Drama, which sounds interesting again your theater side. But mainly the Academic Director and Clinical Assistant Professor in Integrated Marketing and Communications at the NYU School of Professional Studies, where you support more than a thousand grad students and 200 faculty. So you've got a lot of people in here with titles like CMO. We have not had a lot of Academic Directors and Clinical Assistant Professors. So what does that mean, Michael? What do you do?

Michael Diamond: Well, I think of the job of the Academic Director as sort of a mix between the Chair of a department, which would be a classic, you know, academic title and a Brand Manager or a General Manager, you know, of a product. So at the School of Professional Studies at NYU, which is historically really trained, you know, emerging professionals for different careers, there are different disciplines.

And I manage the portfolio of programs in marketing and PR, the graduate programs in Marketing and PR and some Certificate Programs. So the Academic Director has to make sure that, you know, the quality of the programing is excellent. You know, that we're keeping the courses fresh, that we're getting great speakers in and we're working with great partners. You know, we're recruiting high quality students. So, you know, it's got this academic element to it and a sort of business development element to it as well.

Daniel Burstein: I like that, so those are your product lines or your lines of business. And I hadn't really thought of an academic that way, but that's interesting. All right. Well, let's start by talking about some of the things you made in marketing. Like I always have never been like a podiatrist or an accountant or an actuary. But I do feel like as marketers, we're unique, that we make things, we walk away from having made things. So let's start with the first lesson from something you made. You said build capabilities that endure and not just quick fixes to near-term problems. So how did you learn this lesson?

Michael Diamond: Right. Well, you know, the majority of my career in marketing or sorry, the start of my career in marketing was largely from the strategy, research, insights analytics side. And then I as I grew, I got promoted into growth marketing. And, you know, ultimately in the role of the CMO. And we'll talk a bit more about that sort of more traditional creative side and campaign side.

But when I was running strategy and insights, one of the things that I was most proud of was building what's called a strategic segmentation scheme. And it sounds a bit geeky to say I'm proud of that. But, you know, the lesson, you know, to cut to the summary, the lesson from that was, you know, it was far more important to build enduring capabilities, things that people could use. So that they could leverage, that could make them smarter or do their job faster or get them more insight. Than it was to sort of generate quick hit insights for people. You know, so instead of just trying to serve people by answering a question, we really wanted to build more of a corporate capability around segmentation and targeting, etc. And, you know, it was a very engaged, broad, big project.

We, you know, we passed 30 million households, so we had data on, you know, good data on 58% of them and great data from our partners on the other 50% of them. And, and we did lots of ethnography and qualitative research on top of all of the quantitative research. And at the end of the day, we built something which amazingly, you know, a customer service rep could use if they needed to figure out how to upsell or cross-sell. Our M&A guys and gals could use if they were researching a new cable system or geography to go into. You know, the product development teams were able to use it to think through, you know, what the next product portfolio looked like and who the target customer or how to serve the target customer. So, you know, that was very rewarding for me, you know, to go I guess to go broad and to go deep, you know, and build something that lasted.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. So and let me ask you to almost because what I like you're saying, it almost sounds like you're thinking about the value proposition of it going in. So, you know, working with data people, I mean, there are some great ones. But as an example, I'd work with a volunteer with these grad students or doing data science for social good. And it's great seeing students who are very passionate, such smart data people. But then you go in and you'd see it more often of they pull these data points and be like, well, okay, but why does that matter? You know what I mean? What is the value in that, getting to the value proposition of what you're delivering?

So I think you were mentioning at Time Warner Cable this is the point where things were shifting toward the bundling of services like video, internet and phone. So what triggered this? Like what gave you the idea, okay, this is something we need to build to create value? Was it this shift in in consumers?

Michael Diamond: Yeah, I think absolutely. And you know, just a quick comment on what you said before, Daniel. I think when we started the project with strategic segmentation, I could say, you know, we partnered with a wonderful chap called Steven Goldbach who was at Monitor at the time and now is the Head of Strategy at Deloitte. You know, and one of the things he talked to us about and we kept in mind all the time was this sort of balance between insight and action ability. And I think a lot of, you know, projects that analytical people or qualitative researchers can do, could deliver enormous amounts of insight, but may lack a certain amount of action ability.

So, you know, my whole life and I'm sure we'll come back to this is about trying to find what I call the actionable insight, and encouraging teams to build actionable insights. So we did I think we were very explicit about that. Just to sort of geek out slightly more which will answer your question, Daniel. And I'm an English major, by the way, as well. So I you know, Math was something I learn sort of to love and enjoy. But my first passion is English and theater and things like that. But one of the things we also decided early on with segmentation schemes is you have to develop what they call the dependent variable, or put less pretentiously as the business objective.

So you don't just build these segmentation schemes for the fun of it. You know, to sound nice, you build them because you've got some business objective. You're trying to figure out how the various groups of people vary with respect to something. Yes. And in our case, exactly as you identified, it was with respect to bundling. Yes. So we were beginning to emerge into that era where you could buy your, you know, it was slightly before the cell phone services that the cable companies went on to sell. But you could buy a telephone, you could buy video, you could buy Internet connection, obviously. And some at that time were buying one from the cable company, one from the telephone company, one from somebody else, you know.

So the question for us was, how do we identify those consumers who had the highest propensity to some extent to bundle products and service with us. And or better understand those who maybe didn't want phone but wanted the other two products So it did come out of that need and an understanding that, you know, the digital, our connected life was becoming so significant and we as a cable company were able to service so much of that. You know, we really wanted to make sure we understood all of the dimensions of that. And what drove consumers purchasing habits. But, you know, more fundamentally what their needs were and their attitudes and their beliefs, all the good marketing stuff, you know, that you can put into campaigns and but everything from campaigns to pricing, you know, you can really work it.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah, you know, so if you're listening now and you're like, hey, look, I don't have 30 million data sets, I'm a small company, I can't bundle big things like phone and customer. And I'll take just one quick example from us. You know, we found that we bundled our content at one point. We have, you know, we have Marketing Sherpa, Marketing Experiments, MECLABS, we have B2B business blog at this point. And we said like, hey, you know, people are receiving content individually through those streams. We bundled them into something we called the Marketing Experiments Quarterly Research Journal.

So I think there's a bigger lesson I want to get to the data in a second to, but there's a bigger lesson to understand your product mix, no matter what size of a company you have and understand that, hey, you're serving a customer one way, like in the case of Time Warner Cable is cable. But if you're doing a good job servicing them that way, what are the other kind of corollary ways that you can serve those customers? Right. I mean, we're talking about share of customer, right, is that we're talking about?

Michael Diamond: Yeah. Yeah. And we talked about share of wallet. I mean, it is, you know, I mean, we we spent a lot of time with colleagues that, you know, really top class marketing companies like American Express, etc. And, you know, American Express has a very clear eyed view about what at least when I was doing the project, they used to call share of plastic spending, you know, so share of plastic spending was an objective for them. And, you know, so we thought about that, which is, you know, there was a wallet, there was a budget that people household budget people spent on telecoms and Internet connectivity and all those kind of things.

And what might we do to, you know, win more of that share, you know, in in a legitimate and, you know, value additive way. And, you know, it does you know, when you think about these things also, though, from the consumer level, you have to start I think this is the challenge always to be consumer led. You'll learn really interesting things about that. We had a whole discussion about the notion of value, you know, and value means very different things to different people.

You know that there were some people who absolutely could afford the products and services. That wasn't a question of material wealth. You know, having the disposable income, it was just, you know, they demanded good value for money. You know, for other people, you know, perhaps who are more limited budgets or constrained spending. You know, it really did mean probably cheaper or less expensive options at least.

You know, so there's a lot of nuance once you get down to the you know, with exactly the same product and service you know, at the end of the day, the same bits and bytes. Arguably, there's a lot of nuance when you get down to the consumer level, really understanding, you know, their needs attitudes, values, beliefs, etcetera. There's a host of things we studied that allows you then to design products and services and price products and services and package products and services in different ways. And of course influences advertising at the end of the day.

Daniel Burstein: So yeah, when you talk about that nuance, I was watching one of your talks and you use these two words. I just I've never heard them together before. It just grabbed me. Data poetry, right? Data poetry. I love that. I thought was the perfect combination of your background. You got an MFA from Yale and Theater Administration and if you can even just if you're hearing Michael talk, even like we've had a lot of great podcast guests, but no one has been as smooth as Michael so far. The accent part of it for sure. But just I can definitely tell that there’s theater training in there.

But anyway, so, you know, that's maybe the poetry part in and bringing the data into there is you had a background at the London Business School in Management Marketing Strategy. That's where you're MBAs. And so where did you come up with that term, data poetry and what does it mean, is that the nuance we're talking about here?

Michael Diamond: Yeah, well, you know, I studied English as an undergrad at Oxford and, you know, absolutely obsessed by language my whole life, especially the spoken word. And that was, you know, what got me into the theater. I was a lousy actor, but you know, I tried my best and then I directed a few shows and I really enjoyed that. And then I actually ended up managing theater companies, you know, so I love to be around the theater. But I was probably most effective as a business person in the theater and not on stage. But, you know, at the heart is a passion for language and the power of language. And what poetry does well and I'm going to butcher this, I forget who said this, it will probably come back to me, probably Coleridge or something. It was what oft was said, but near so well expressed.

Yes, so oft was said, but near so well expressed. So what do they mean basically is, you know, poetry has its lovely way to, in a very compact and elegant way to put information and impact into a sentence, you know, and also give it beauty. And what I found when I was dealing with data is that, you know, the folks around me who were not trained in data or data science or particularly interested, you know, you were much more powerful and effective, if you could tell a story, a data visualization story or a, you know, a story that sort of almost attacked the emotions and got the emotions. In the way that poetry can kind of get under your skin. So that was the idea of data poetry. And more broadly, and I think you started to reference there is, you know, the longer I've been in marketing and seeing some of these, you know, back and forth between is it data or is it, you know, is it brand or is it performance, is it creativity, or is it technology?

You know, the more you realize it's both, it's got to be both. And so we you know, at NYU, where I'm teaching now, at the heart of what we teach is this notion that marketing is human centered and data driven. Yeah. And so I was trying to capture that a little bit in the idea of data poetry, and you're trying to balance those things, but also bring out the beauty. I think that talk came from a talk I was giving about data visualization. And data visualization obviously has an esthetic quality as well, which, you know, which is they're nice to look at good data visualization. So that that felt to me a little bit akin to poetry as well.

Daniel Burstein: I like that. I'm going to use that. Well, let's talk about a lesson from the more human centered side. You said tackle problems with integrity, self-reflection and some humor. And as a creative, I just love the campaign that you had behind this. So tell us what you did as the acting CMO of Time Warner Cable, how you how you learned this lesson.

Michael Diamond: Yeah, well, you know, and then like all the efforts that, you know, we described their done by teams, you know, broad groups of wonderful people that we get to work with. And I you know, I would never put myself in as the sort of creative brand genius by any measure. I had wonderful, wonderful people in agency to work with. But one of the things that was very clear to us, once I was Acting Chief Marketing Officer at the end and had sort of responsibilities more broadly than, you know, research and insights and things like that. Was as hard as we tried. And we really had to develop new products and services and really wonderful, innovative, you know, extraordinary services that leveraged in large part, I guess, the broadband infrastructure and, you know, television on mobile devices, you know, I think Time Warner Cable was probably the earliest, or one of the earliest doing a whole host of these kind of things over IP.

You know, at the same time, it was probably fair to say we were still tackling some perception issues around service and reliability and all that. But ironically, we actually knew we had made significant investments in those things. And our numbers in those areas had had increased. And we’d done well and, you know, we improving, but we had a sort of reputation. I guess today we would use the word reputation you know, that we had to deal with. And so we developed a series of campaigns that for the first time sort of made fun of ourselves and sort of acknowledged the problems honestly.

And said, you know, we're working on these things. But it also did it in a humorous way. And I think in some sense, you know, I it would be entirely wrong to say it was somehow my ethic that came through, but that was entirely consistent with the way I often feel about life is, you know, you have to be honest and own up and fess up, you know, to things that you may have done wrong or a mistake you may have made, but you can also do that with humor and you know, a good a good spirit.

And I just think Time Warner Cable at the time was doing an amazing job of really honestly, you know, reviewing and proving, communicating. You know, I think we did a great job. And I believe the last year I was there with, you know, one of our very best years. And shortly afterwards, you know all of our various CSAT (customer satisfaction) scores, you know, shifted significantly. So you know, that collective effort. And again, it's never one area. But I think between all the work we did in engineering and customer service and product development, and then on top of that, to support it with marketing was, you know, made a difference. And we did it in a certain way, I think.

Daniel Burstein: Well, I'm a writer. I'm a creative, pitch me one of the concepts, come on! Real quick, though you mentioned the improvement. I saw it in one of the articles written about it, 4.9% improvement in revenue that quarter. But, c’mon see your pitch, Mike. What was one of the concepts do you remember?

Michael Diamond: You may be really pushing me hear a bit, but what I remember was just this very, very cool, dude, who was, you know, bursting out and dancing to the hold music you know. So this idea that, you know, sometimes when you called in, you might be on hold for a very, very long time, you know, which I think is, you know, is more the exception than the role, clearly. But it was the things that would make the late night talk shows. And so we had some funny commercial with this chap listening to our hold music bopping around and dancing around. And yeah, it was I think it was very you know, it was very one done. It was sincere and it was humorous, and the chap playing that role was perfect casting, I think.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. Well, I think really lesson learned here too, is, you know, I've been in so many value proposition workshops with business leaders and there is a very big difference between value perception in the audience and the potential customer, and the actual value that's being delivered. So, even though, you know, Time Warner might have improved significantly in the value they're delivering, customers might still have the perception from several years ago. And that's why a campaign like that is so important. In this situation where the company is making a transformation. But in any company, there's so many value proposition workshops I've been in where they're doing something behind the scenes or they're doing something, you know, in a factory or in development or whatever, but nobody knows it, right? I mean, that's the whole point of marketing. Communicate that value.

Michael Diamond: Well, yeah. And I also think, you know, there's a couple of old, you know, addages said, you know, one is about people will remember not what you said or did, but how you made them feel. You know, I think very often brand experiences or your interaction with a certain value proposition is ultimately about how it made you feel. And that's sort of what you remember a lot more. And that's probably even more true with service brands, you know, where so much of it is about human interaction.

But the other element and it kind of goes back to this question about data poetry, is you know, and it's a quote I like a lot and, you know again, not intending to sound pretentious, but there was a Roman Orator, a guy called Cicero, you know, many people read for his wisdom and everything. And one of the things he said that I absolutely love is he said the effect is in the affect. And what he meant by that was essentially, you know if you can hit people at the emotional kind of heartfelt level, you're going to have a lot of impact. And so I do think that, you know, a lot of marketing I mean, obviously, I'm not saying anything new here. A lot of marketing has traditionally worked at that level to try and understand, you know, how to move some levers around emotion and affect. The build I would give you, Daniel, these days, and I think it's a genuine conversation is you know, is that we've moved probably as well from that to this broader idea. People talk about moving from value to values.

So I think now the other element is a little bit more cognitive you know, which is about, okay, but what are you doing for the world and how do you show up in the world as a brand and, you know, what's your purpose, your social purpose? And again, most many of those things are also affect related because you want to feel good about yourself are using or buying a brand. But they are also a little bit more cognitive. I think people are thinking about, you know, what is this brand? Not quite just how does this brand make me feel, but also what is this brand or this company doing in the world? And, you know, so that's a new, I'm sure it's not new, but, you know, that's the thing that a lot of us are thinking about and we're trying to educate students to be more aware of that as they as they think about their practice as marketers and PR people you know.

Daniel Burstein: Very true. And so if you're hearing this and you think it was very B2C, I think we've got really a great B2B example coming up about how you did something not exactly the same, but kind of also made sure you changed the both value perception, actual value delivered, and maybe even values of a B2B event. So you said the lesson was trust yourself and your instincts, especially when you feel passionate about something. Which ties into values very well. Yeah. So tell me, what changes did you make at this B2B event?

Michael Diamond: Well, actually, you set it up in a really nice way, Daniel, and in a way perhaps I hadn't thought about before, which is you know, so the, you know, anybody who's listening, who spent some time in cable television, you know, on the programing or the other or the network side or the you know, the system side will be familiar with organization called CTAM. And it's a wonderful organization. It's basically the cable marketing group. And, you know, I try to participate as much as I could when I was running insights and research and certainly later as well. But I would go to what was called the research conference each year and, you know, it was a wonderful conference. But my question at the time was, you know, it felt a little bit like we were talking to ourselves, you know, so a lot of, you know, cable research people or TV research people would be there.

And I also felt at some level and maybe it was because I'd sort of just taken on this role and may have been candidly through with my own ego. You know, I felt like, well, you know, we're more than just research. You know, we first of all, we're insights, you know, and so we talked to the leadership of CTAM about rebranding the conference you know, and I had two wonderful colleagues with me working on that from ESPN and I think Viacom networks that I'm blanking for a moment on the second. But, you know, so the three of us sort of decided we would, you know, rebrand at least the insights.

And then the second thing I think was this idea that we wanted to sort of elevate the role of insights themselves and make this a conference that not just researchers would come to or, you know, the CMO would say, Yeah, well, why don't I send my VP of Growth Marketing or, you know, my VP of Brand Marketing or something like that, that he or she would see this is not just a place where researchers are going to talk, but actually where actionable insights, back to that topic were going to be generated. And then the third thought none of these things actually answer your question quite yet. But the third thing, Daniel, is that we also had a sense here, back to this idea that we shouldn't be talking to each other, that we should bring people in.

So we were able to bring in you know, wonderful people like Dawn Hudson, who at that time was the, I think she just stepped down actually was CMO of PepsiCo was certainly the CEO, I can’t remember. But she was a wonderful help. So she went on to be the CMO of the Ladies Professional Golf Association just a wonderful individual. But by pulling people like her in to have conversations with cable marketers, it felt to me it was going to be much more useful you know, to bring some of those, you know, FMCG, consumer packaged goods type thinking into our discussion. So that was sort of the three things we try to do, you know, shift from research to insights, elevate the role of insights to be more operational or business focused. And third was to bring in new voices.

So, you know, I had sort of thought this through before and this is sort of starting to answer your question perhaps a little bit, which is, you know, that was kind of my instinct, you know, going in. But I wasn't quite sure it would work or I wasn't quite sure everybody else would agree with me. And you know, so it was a bit of a leap of faith to sort of, you know, push on this and trust my instincts. And I felt like I was on to something. And as I said, I was very lucky to work with somebody like Artie Bulgrin who was wonderful chap at ESPN and others to make this thing a reality.

And they shared that vision. But it was it was rewarding, you know, to recognize. And then what happened actually was that the people cloned a lot of our content to use for other conferences and things like that. Actually sort of more senior executive conferences because they kind of got what we were doing. We even were one of those early conferences, I may not be able to paint the word picture here for you, Daniel, but we had this fantastic cartoonist at the back and he was cartooning the whole time with what people were saying.

So at the end, there was this wonderful scroll, huge scroll that went around the conference room. And we gave people copies of it to take home or whatever later. You know, so we tried very hard to make this an event that was engaging. And, you know, the satisfaction ratings were off the roof and the attendance was very strong as well. So, you know, net net, I felt like, you know, I had a chance to articulate vision, drive some change, you know, work with great colleagues and deliver a very hopefully memorable experience.

Daniel Burstein: Let me dive in a little deeper because you're saying this very eloquently, and I want to say this very non eloquently and very directly to the audience, because you mentioned tackle problems with integrity, self-reflection, some humor. So I'm guessing. Oh, I'm sorry. You mentioned trust yourself and your instincts, especially when you feel passionate about something. So I'm guessing you were getting some pretty big pushback and so what I hear you're saying is very eloquently, what I hear is this was a pretty boring research conference with researchers and we needed to expand it because we're the cable and television industry and we're attracting marketers and advertisers. And we really needed insights into our audience. And so did you get some pushback from the other kind of more research oriented data driven hey, let's talk about statistical validity type of folks there?

Michael Diamond: Well, you know, I probably wouldn't agree quite with your characterization of my work, Daniel. Because as someone who loves research. I don't think the conference was boring necessarily. I actually really don't. I mean, certainly I love going to the conference, but I think it had more potential. You know, it just had an opportunity to play a bigger role. So the pushback, I think is usually that you get again, I'm you know, I'm going to probably come down as your most pretentious interviewee this week.

Daniel Burstein: Listen I was going for some of Cicero's affect when I said that.

Michael Diamond: All right, all right.

Daniel Burstein: I was learning from you, but go on.

Michael Diamond: I can match your Cicero, I will see you a Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer was a philosopher? And one of the things he said is all truth arrives in three stages and trying to remember the order he said first it's resisted, then it's ridiculed and then it's finally seen as self-evident. So and I think and I explain that so this is if this has been my experience throughout life, you know, you try and do something new and at first people say oh no, you can't do that because you know it's going to screw up the system or that'll delay our ship day or you know, we've never done it like that before.

You know, there's always a whole host of reasons, you know, legitimate, you know, at some level reasons because someone said to me all change requires somebody else to do something different. You know what I mean? Like someone is going to like, oh, G-d, I got to do something different. So first it's resisted. Then what happens is when they see you persist they'll say things like, oh, Michael with his clever ideas. And, you know, it's just one of those things again, you know? And then finally, once the thing is in place and it works, that everyone said, oh, yeah, well, you know, we all did that years ago. You know, we've been doing that forever. That's nothing new. And to some extent, that's fine. You know, if you know that that's going to be your experience walking in, I think that's fine. You know, you just got to sort of not lose each of those different stages. And you know what I would say? I don't think it would be fair to say there was massive resistance to the change. But, you know, there were people who'd already made the logos and the brochures or whatever it was, you know, and they, you know, they wanted some consistency in their lives.

And you know, and people felt comfortable with the conversations they were having, you know, but I think everybody ultimately embraced it quite quickly, you know, and got on board. And we were able to elevate that community of researchers who was still, of course, the core. But you know, it gave them a bit more standing. I think that's actually what's happened in the industry. You know, I mean, the people who bring you insights are the people you should treasure. You know, those ones you really whether it's qual or quant, if you've got really high quality people in your institution or your groups that are developing really you know, actionable insights that you want to nurture them and develop them. So I hope we achieve that, you know, without too much resistance.

Daniel Burstein: Well, I think you did a great job of explaining what can happen when you try to change something on the front end. Anyone who's worked in change management can see that. But I think on the back end, too, after the thing goes live this, you know, then you get the feedback and one thing. So we had a great podcast interview earlier with Nicole Salas. She's a CMO of Kiddie Academy, and she talked about a campaign that they were running a TV commercial campaign on PBS Kids. And she got this long handwritten letter from someone who just didn't like the music and just was tearing it apart. And so I tell you, what I've done sometimes in my career is you hear that one loud voice, then you're like, Oh, no, it's not good. But what she did she framed the letter. They made memes out of it. And because what they realized rightly is, hey, we elicited a response. That's a positive thing.

And so we're talking about data don't get too deep. They're just idea of statistical validity and outliers. Right. And so when you're looking at actual data with the smart insights person, you can see that statistical validity where they're outliers. But when you try to make a change or when you have a creative concept and you have one really loud voice, sometimes we overemphasize that voice, right? Sometimes we hear that loud voice. We're like, Oh, no, maybe we need to rollback this change. Yeah, it's part of the equation.

Michael Diamond: No, I think that's a super important point, Daniel, but if you don't mind me building on it a little bit, I think it's a couple of things. So I definitely agree, you know, I think you just have to have common sense, but certainly more statistically minded people will understand, you know, that one loud voice could be an outlier in the data set and doesn't necessarily represent the data set.

But at the same time, the qual side of me would say, you know, lots of things. One, you know, all complaints are a gift, which is the old there's a book called that, you know. And secondly, you know, a lot of the study of innovation, as I'm sure you know, is actually looking at people who are outliers and understanding how they use your product.

You know, so you want to know about the chap in the basement who's hooked it up to seven different other things and why this and that? Because that might actually be an interesting product, you know. So, you know, I'm not a person who naturally resists outliers. You know, I actually want to hear what they have to say because they may bring insight. So, you know, I think you have to sort of deal with that in moderation. What's dangerous, I think, is if decision makers in companies use like, well, the last person I spoke to said X, you know, so, you know, that's a bit dangerous, clearly. And the other thing that's often dangerous, you know, I don't want to disrespect anybody's instincts because there are some who have enormously good instincts. But when people start to talk about “I”, when you're talking about marketing campaigns, you know, well, I like this and I like that.

You know, that's a little challenging, you know, because you are not the customer necessarily. You know, most CEOs are not the customers. You know, directly of their products and services. So some humility, I think that goes back to your conversation, your point about humility. I think you need to have some humility that you know, however loud your thoughts are, they you know, they may not be they may not be representative. So I think that's one way.

Daniel Burstein: Well, I love to what you say about it too, I remember that too before. I is one of the worst words in marketing. So, you know, as a writer, I'll come up frequently. You get it. You know, some like a long copy ad or a long copy sales letter. Long copy for brochure. And a designer will come back. No, I would never read this, I would never red this.

I even had one time I got the proof back from a printer and I saw my copy just ended in in the middle of a sentence. And I went to the art director and said, oh, you know, there's some mistake here. Everything's like, no, I just cut it off. It didn't fit. And, you know, I would never read that much. And you know who would that read that much? Let's say, this is an example, a long copy ad for a refrigerator. You know, who would read that much? Someone whose refrigerator broke in their shopping for replacement.

Michael Diamond: Exactly.

Daniel Burstein: I wouldn’t and you wouldn’t our fridges work. So yeah, that's a really good point to keep mind. Okay, so when these things come up, right? So when you're passionate about something and when sometimes the leadership doesn't go with it, you have to, and this gets into our next lesson, speak truth to power. One of the most important yet most difficult things we can all do in any career.

So we're going to shift now into some lessons from the people that Michael collaborated with. Right. Because we as marketers, there's two things we did. We build things and we build them with people. That collaboration is so important So, Michael, you were telling us about Don Logan, the co-CEO of Time Warner, and he taught you to speak truth to power. How did Don do that?

Michael Diamond: Well, you know, if any of, you know, Don Logan and, you know, maybe many of your listeners were in the advertising industry and the magazine industry, you know, and come across Don Don was the very esteemed CEO of Time, Inc. for you know I think ten or 11 years, and had run Southern progress before that. And he came over to, in the various different sort of mergers that were going on with AOL and all of that sort of movement going on.

He came over to be co-CEO of a of Time Warner Inc, and his portfolio was to run all of the essentially subscription based businesses, which included AOL, Time Inc. magazine and the cable company. And then Jeff Bewkes at the time was the other co-CEO, and he ran the studios and, you know, the music labels and the networks and things like that. HBO, of course.

So, you know, and Don, when he came over, he and I had worked together before in different guises. And he asked me to be his Chief of Staff which I was absolutely, absolutely thrilled to do. And, you know, early on, I remember one of the things I had to do was sort of work with him on a monthly and quarterly basis, looking at people's budgets and strategies and, you know, and working with the CEOs and the CFOs of those companies to pull things together. And, you know, I think I put together a nice deck early on and was walking in through the numbers.

And Don is just such an extraordinarily smart, you know, smart man and intuitive businessman and very human, you know, kind of individual as well. But just so you know, just a whip, smart person. I think he literally, is a rocket scientist, you know, that's kind of what his graduate degree was in. And, you know, I could tell by the questions he was asking me about these numbers that he knew far, far, for more about the businesses than I did. And possibly ever would, you know, and I had as much to learn from him as I could possibly share with him. And I sort of said to him, I think I was way too candid. I seem to remember I said something like, you know, Don, I don't know if I'm going be able to do this job, you know, because, you know, you're much smarter than me. You know, all these things, you don't need me, you know? And he said to me and I thought it was a wonderful thing. He said, look, you know, in a room of various people where everyone's going to have an agenda, I will know that you'll always be the person that will speak truth to power. That you will tell me straight, you know what you feel, what you see, what you know, what you hear and things like that. And I said, and, well, that's the job I can do because I felt very comfortable that I could do that job.

You know, and again, it wasn't to impose my opinion or to second guess anybody. It was just to say, I'll give you a fair assessment of what I see and I will be comfortable saying, you know, the truth, you know, or at least as I perceive the truth. You know, I wasn't going to hide anything or gild the lily, as they say, or anything like that. I just was going to, you know, tell the truth.

And I, I think that's an important role. I think it's very challenging for you know, young professionals, even perhaps more senior professionals to do that. Because we all have a mortgage and kids we want to put through college perhaps things like that. So, you know, I also recognize that, you know, and this is a lesson perhaps I learned later in life and would add to the idea is that, you know, it's not necessarily always important to be right. It's more important to be effective and have impact. So, you know, I believe in speak truth to power, but I think, you know, am I always evolving? I think you also have to moderate that with, Okay, that's true, but also, you know, how do you have impact and move things forward? It's not just about being right. You know, so that's a sort of gloss on the idea of speak truth to power.

But I think it's very important I think if you're going to have a long career in any industry or company, you need to be known as somebody who was a straight shooter, you know, not political, not saying one thing to one person, but, you know, being honest and open about what they see here and believe, you know.

Daniel Burstein: What I look at from the opposite way to I mean, what a great leadership lesson from Don for anyone listening now who manages anyone to be able to have that conversation with them and to validate them in that way and say, hey, here's what I need from you. And for them to do that. Yeah, sorry go on.

Michael Diamond: No, no, that's a wonderful point. Yeah, I think that sort of some of the aspects of Don I was trying to get to, you know, I think he really was a very empathetic leader before we ever used the word empathetic, you know?

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. And to be able to speak truth to power I’m going to say you need to be able to trust yourself, which is our next lesson. And I love that it came from the opposite direction. You learned it from Victoria Stapf, who was your executive assistant at Time-Warner. Right. So how did Victoria encourage you to trust yourself?

Michael Diamond: Well, you know, Victoria is one of these wonderful colleagues, you know, who we work with and collaborate with, and but also have this capacity to just remind you of the important things in life. And, you know, Victoria or Vicki, you know, she and I worked very closely together. And I guess at some point in our chatting together, about something, I had given her some counsel, a similar counsel about trust herself. But one day I was definitely struggling. You know, I think I'd just moved into a fancy new office or I had some new position. And, you know, I had to sort of try and figure out how to navigate all of the various trappings and new responsibilities and also things like that.

And you know, I came into work one day and there was this little rock with the words trust yourself, you know, just engraved on the rock and it was just so empowering. And it really made me sort of pause and say, you know what? You know, you've got this, you know, not, not in an arrogant way. But just, you know what? You actually have it within you and you just got to trust yourself a little bit. So I've tried to pass that on even to my kids. I think I gave the rock to my daughter at one point, you know, so I have tried to sort of pass that wisdom on.

But I think that was a very important lesson to learn from you know, somebody else who was looking in. I had similar counsel at one point who someone said it's a similar idea. They said, borrow my reality. Yeah. So it's this idea that, you know, sometimes you need you just use the word validation earlier. And I think it's an element you need sometimes a third party or someone outside of you to remind you, you know, that you know your instincts are good or you know, the world doesn't look quite like you think it does. Or, you know, people's perception of you is not quite what you think it is. You know, you need that kind of external validity. So I thought that was a very powerful lesson for me.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah, I think that's great when it comes into the kind of those internal conversations. I think another way sometimes we don't trust ourself is, you know, so there's a lot of tools out there and there's a lot of software out there that I've seen, especially a AI driven software where it's just kind of like, hey, trust us, this thing works and there's inputs and magically it just kind of gives you the answer.

And so, for example, we have a free digital marketing course. We have tools in there, but they are thought tools because the idea is that the marketers, they should trust themselves. Here's a framework, here's the methodology, here's your heuristic, take these free thought tools and trust yourself and use it to figure it out. As opposed to, you know, just what I worry about when I see some of those other tools out there. It's, you know, what a good researcher would do is not understanding the methodology behind how it's giving you the answer. Right, you are just supposed to trust some technology.

So as a researcher, I would think to that kind of trust yourself comes in huge to be able to understand or an insights man if you'd prefer. Yeah you know what methodology went in and why can I trust this data when I'm presenting it and presenting as an insight.

Michael Diamond: Yeah well I think I mean you know trust is a huge word. And now obviously, I've been working a bit with Antonio Lucio, you know, who, you know, probably well from his days at Facebook or Pepsi or Visa or, you know, an extraordinary human being. Another extraordinary human being. And his passion is about the idea of building trust and how companies, you know, really have to put trust at the center of a lot of what they're doing, partly because other institutions like governments, etc., are not necessarily delivering in ways that we need to sustain the climate or effect social change or whatever.

You know, there is a clearly new role for companies and by extension, marketers and, you know, shameless plug. That's kind of this new executive masters that we're launching in the fall is sort of around that, it’s like how to help marketers think about things like these questions of trust and, and purpose and integrate it with all the skills they have as marketers and PR professionals to become leaders.

But, you know, this idea of trust is very critical for all of us today. And I think you're right as well, which is for anybody to put confidence in you or to trust you, the first thing is you need to deliver on your promises. Yes I mean, that's the simplest definition of trust is to deliver on your promises.

But the second, I think, is this element you were talking about, which is to, it's almost what was the famous saying, Trust but verify. you know. You do need to also understand I mean, we as consumers in this information rich, or you know, some call infobesity. That there are you know, I think it's okay to trust companies or at least to say, you know and know there are very many external ways to validate this now that you know they are making their best efforts to do X, Y and Z.

But you can also verify and you've got to be intellectually curious and you got to be engaged, you know. And I'm sort of mixing the role of a consumer and a marketer here. But, you know, I think as a consumer, that's true. But I think as a marketer, you always have to ask yourself, you know, what is the quality and the nature of the information I'm receiving? You know, what was the and this is the you know, this is what scares data people, I think appropriately so, is, you know, well, who is getting measured? And, you know, I think we may talk about this a bit more, but, you know, the great anxieties, legitimate anxieties of groups that look at a lot of data science and how it's being used today. Is because the data sets that are driving some of these decisions don't necessarily include people of color or enough women or take into account regional differences or any host of things, you know, because the data just wasn't collected that way.

And so that sort of question of trusting the data, you know, I think sometimes people are like torturing the data. You know, I think that's very appropriate. You know, we should, we should be asking those questions and we shouldn't allow ourselves to see a machine or a black box as somehow, you know, a better answer because, you know, someone told you there's an algorithm and G-d forbid they said it was Artificial Intelligence. Then we all have to bow down, you know, or machine learning or something like that. You know, you’ve got to know and understand what's under the hood of it, you know?

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. How does this thing work? But so getting to that trust, we have one more or less one final story, and I think this is really applicable to maybe some of the more entry level people listening. So I know when I started as a copywriter, you know, I mean, it's not like being a doctor where there's a residency or some like where there are some official kind of path you have. I mean, I had an internship.

But, you know, one day I was a college student. The next day I was a copywriter in an ad agency. And people looked to me for answers. And it was the weirdest thing. You know, you start as a student all of a sudden wait a minute, you're supposed to know things. And so it seems like earlier in your career you had a similar experience from Janet Harris, the Director of Development in the Manhattan Theater Club. She told you, we hired you because you are smart, you have our support, and we expect you can figure it out. So I think that was at another level of trust when you were starting out?

Michael Diamond: Yeah, I guess so. You know, working, so my first career, yeah, I went straight from undergrad to grad school at Yale, and I studied in the theater, wonderful drama school there. And I studied theater management. And my first real job, I guess, was at Manhattan Theater Club in New York, you know, phenomenally well run institution run for years by a man called Barry Grove and Lynn Meadow, who was the artistic director. It's just a wonderful place to be, frankly, as a young theater manager. And I worked with Janet Harris, who was the Head of Development. But when I walked in the door, I think I was so overwhelmed by all this talent that I just convinced myself where they had all the answers. And, you know, it was almost kind of like a test you know, I was it I could you know, we in academia, we sometimes talk about guess what's in teacher's head. You know, it's like, you know, the instructor asked the question and everyone in the class feels like, oh, I'm just trying to figure out what's in his or her head, you know?

And I felt that a little bit, you know, like somebody else knew the answers. And my job at that time was to organize all of what they called individual fundraising, you know, so patrons and donors and all that sort of thing and start some telemarketing campaign or tell a fundraising campaigns. And I remember at one point, you know, just struggling with that and, and trying to come up with a solution to a problem. And I think I literally was in tears. You know, talking to my boss and saying, you know, I don't know if I got the answers and I don't know if this is right or wrong or what you want. And, you know, I was clearly a little overwhelmed and she said to me, you know, like essentially it was a sort of trust yourself.

She said, look, Michael, we hired you because you're smart, I actually interned with them for a little while. And so they knew me already. But, you know, we hired you because you're smart. You have our support. You know, whatever you need is basically what they they're saying is, you know, if you need budget or, you know, people like, you know, but it's your job to go figure it out and then come back to us with a recommendation.

And it was extraordinarily empowering. It really was empowering. You know, to be told, I mean, it could have had the reverse effect, which it could perhaps of overwhelmed me even more, you know, to feel there wasn't necessarily an answer. But it really was empowering because I felt it taught me something that I try to share with people, you know, 30 plus years later, which is a lot of junior people in companies. And as you said, you may have listeners, you know, who are just beginning in their careers. They always assume that the senior people have the answers. You know, like someone up there has figured this out, you know. And I can just tell you and I, you know my career was, you know, very rewarding and hopefully accomplished. There’s not, you know, many other probably distinguished people you've had on your podcast, but, you know, the people on top don't have it figured either.

You know, they too, are asking these questions and what's more empowering is if you actually realized, generally, you know, they hired you because you're smart, and you know perhaps you youn or perhaps you come from a different industry or perhaps you have a different perspective. Whatever reason it is, you know, they hired you for you and they're looking for you to come up with some of those answers, you know, and so as soon as you can get through, I think there's moment of feeling like, well, somebody else has the answer. It does two things. One is I think it stops you feeling, you know, sort of sheepish about your own answers or, you know, like, oh, my answer can't be worthy.

The other thing is it actually tells you I got to jump into gear and do something. Yes. Because there isn't an answer I'm supposed to be following. You know, actually my job is probably to figure out the answer, you know, so, you know, again, it's all nuance. People have different jobs. I was super lucky in my career to have jobs which were, I guess, characterized more like knowledge management type jobs. So that, I guess, is what I was paid to do to think and develop new ideas. But it was a very powerful insight, you know, that, yeah, you're here because we wanted you to be here. Your ideas of valid and we don't have the answers. You figure it out. You know, that was that was empowering. Very empowering.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. I mean, I love that you said that we talk about this imposter syndrome. I'm sure everyone heard imposter syndrome. And it's a great quote. I'm probably going to butcher it from Barack Obama, but he talks about, you know, when he went from community organizer all the way up to president of the United States, you know, it's the same jokers in the room yeah. No one has the answer still. And that kind of really shocked me. I mean, I, I felt that in my career. And I think that is, you know, hopefully for the podcast listeners, that is one thing that has hopefully been helpful in this podcast. You know, Michael, you're not the first person to bring this up. I was interviewing Aaron Diamond, sorry, Aaron North, who is the CMO of Mint Mobile.

And he was saying when he first started at Taco Bell earlier in his career, the scale there was so massive of everything they did. And so the impact of his decisions was so massive he kind of froze up at first. Before his boss told him, hey, trust your gut, we hired you for a reason. You're the guy that knows. That's the thing that surprised me. I like that you mentioned that. When I started early, my career as a copywriter, you know, in the room they would ask me and I'd look around like, okay, who knows the answer? I was like, oh, wait a minute. That's right. That's my job. I'm supposed to know the answer.

Michael Diamond: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. No, I think you know, the word gut just makes me think of one other thing, which is and, you know, I had a good opportunity when I was at Time-Warner Inc. I think even. Yeah. Time-Warner, Inc, to you know, help the HR folks with trading and leadership and development programs. And one of the things we used to talk a lot about was head, heart and guts, you know. I think the combination of those three things is, you know, we may talk about this bit later about, you know, that's one of the things you think about as a leader is how do you balance the head, heart and gut, you know, and you need a little bit of bit of each, you know, passion, intellect and instinct perhaps.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. Well, let's get to one more lesson. You said this was from Judith Harrison, EVP of Global Diversity Equity Inclusion at Weber Shandwick. It's not just the how and what of marketing and PR but often who is in the room. So how did Judith teach you this?

Michael Diamond: Well, you know, I've had the great privilege at NYU to work with an advisory council of wonderful leaders in Marketing and PR, including Judith. And, you know, I've been an admirer of her work around diversity, equity and inclusion. She led the various very big effort that the PRSA, you know, the Public Relations Society of America led probably, I guess, five to eight years ago around diversity and inclusion.

So she she's really just a wonderful presence and thought leader in this space. And someone I've had the privilege to sort of talk to. And we were in the heat of a conversation about what we're teaching at NYU. We you know, we think a lot about what programs we offer to our graduate students. In fact, I think we were actually talking about this new executive master's that I've mentioned and how to put it together and what we were teaching and she said, you know, I think very smartly, but also don't forget who is in the room. You know, meaning, of course, that, you know, the modern marketing, modern PR discipline has to be as cognizant of, you know, the diversity of voices and, you know, the way by which we create roles and create opportunities for people of color, for women, for LGBTQ, for, you know, veterans, for, you know, people with access issues, etcetera. It's just this reminder to all of us that you've got to think about who is in the room, whose voices are being heard who's being seen, who's part of those decision decisions getting made.

And you know, how to enrich the conversation with more people or more diversity of opinion, I guess. Not just more people. And that was very powerful to me. You know, I think I would hope that I knew this, but you always need to be reminded of it. Because it's so easy just to you know, obviously, most of us kind of center our wealth from who we are and the privileges, you know, and backgrounds and experiences we've enjoyed. But it's just so critical then to put, you know, more voices in the room. And so I really appreciated her saying that. And it's very much a watchword of our program, both recruiting students, you know, staffing the speakers we have, the kind of partners and projects we work on. You know, we really are trying to be as thoughtful and intentional about that as we can.

Daniel Burstein: Yeah. And I like that. I mean, I hear the word room very broadly. And it is just something as content creators to think about. So, for example, when we create content we put out a very broad net out there and ask people to come to us, you know. Because something that can happen is a content creator. If you just build relationships with certain folks, you just have a very insular look. So whether we did the last blog post, which was just this real group blog post writing effort of, you know, what was the final thing you would you would say in a blog post if you were about to die, or even with this podcast where it's very application based, I'd say, you know, if anyone out there is a content creator, look at how are you finding the sources for your content? How can you open that up beyond just the, you know, relationships, you know?

Well, I know, Michael, you have to be getting off to an important meeting up state. Let me ask one more question before I let you go, though. I think you've kind of hinted at this as we've gone through, but what are the key qualities of an effective marketer?

Michael Diamond: Well, you know, I think I would start by saying intellectual curiosity. I've always felt, you know, good marketers are just passionately interested in the world around them and consumers and consumer behavior and product and design and you know, they don't have any limits. You know, they're sort of sensing they're out sense making, I think, is sometimes the term used. But, you know, they're out there collecting all this thick data, thick to description, you know, like really trying to be curious about the world around them, culture, things like that. So I think that number one is absolutely a sort of an intellectual curiosity.

Number two would be a balance. And we've talked about this between, you know, a human sense of view, a qualitative view , a creative view, whatever. And the data driven or an analytic or a structured problem point of view. You know, sometimes they call it the poetry and the plumbing or, you know, the math and the magic, you know, whatever you want to use as your frame of reference but I think all modern marketers, and again, central part of what we teach and why you need to have that discipline.

And I think the third thing, again, we've talked a little bit about this is this idea that you either need to have a bias for action, which I think is an interesting way of articulating it, or at minimum, you need to be thinking about impact. So a lot of what we do, you know, can fill a rewarding and interesting engaging. But at some level, we have to measure the impact, not just the outputs and, you know, what activities we're working on, but really the impact.

So I think marketers who, you know, broadly, intellectually, curious, culturally curious around you know, the whole ecosystem that surrounds them, that balance, that sort of data side and that more creative side. And then who are always focused kind of on ultimate having impact. You know, on top of perhaps some core leadership skills that we probably spent most of the time talking about. You know, I think that that's what I would look for, or I’d hope at least I've tried to develop in my own career. So let's put it that way.

Daniel Burstein: I think it's great to see someone who has experience with research, who's an academic to use that word impact, because that's what sometimes we hear in education and research. It's not focused on the impact, the reality of actually putting it into actions. I love hearing you say that.

Michael Diamond: Well, that Dan, if I could jump in. I think that is the one thing, you know, and this is you know, I'm like Cassandra in the wilderness here. I sit on lots of these lovely CMO councils. You know, the ANA has been kind enough to invite me to the CMO Growth Council. I go out to CAM you know, I sit in all these meetings, you know, and I'm sitting there as an academic now or you know, and I use the word loosely, of course, but, you know, sitting there as someone who comes from academia and everyone complains about the universities and, you know, they're not teaching that, not this.

I think the reality is that's not really true anymore. You know, or at least I can I obviously only genuinely speak for NYU and the programs we teach at NYU, but we're entirely focused on impact. You know, we're entirely focused on the practical application of X, Y and Z. You know, we're not teaching students to write book reports and do Multiple-Choice quizzes.

And remember, you know, how to define things. We're teaching students, or more important than helping them learn, which, you know, is an important but subtle difference. You know, helping them learn how to build a marketing plan or, you know, create an actionable insight or generate a media plan or, you know, calculate customer lifetime value or whatever it is. You know, we're teaching them how to, you know build a competitive strategy, you know, the things that they will need to do on a Monday morning.

And I think that, you know, the one thing I love I'd love to find a way to have that conversation, which is I think the gap is probably not as broad as people think it is between what's being taught in universities and what the industry needs. But obviously, you know, if that gap is greater than I perceive, I'd love to have that conversation. But, you know, that's certainly at the heart of what has made doing my job at NYU so wonderful is to try and marry the practical experiences I've had and a sense of what I think might be useful to CMO's and potentially CCO’s as well with whom we serve. And doing it in an academically rigorous way, in a pedagogical way. You know, there's learning about how to teach people and how people learn and we want to do it well. But, I think that, well, at least the project at NYU, you know, across these different degrees that we offer and certificates that we offer is really this applied professional education, you know, in the real world.

Daniel Burstein: Well, I think that ties together all the threads of our conversation nicely, right? Because on the one hand, is it the value perception versus actually value delivered challenge like you talked about having a Time Warne? Or is it hey, hearing these voices of these customers are the outliers? Or are these people I really need to learn from because there's, you know, maybe something we're missing or some new product or way we can deliver value. So I think that's perfect. I think it's funny how a career comes full circle.

Michael Diamond: Well, it's even the other thing you touched on, which is the folks sometimes saying that in the room are really going back to their own experiences 10 to 15 years ago as students, you know? So they're sort of saying, well, you know, when I was a student, you know, whereas, you know, I think if you work with us, not us, but big us, you know, academic education. You'll see that for many of these groups or certainly the professional schools, the ones who are more oriented to this. You know, we're really thinking about building capabilities and training emerging professionals in marketing and PR and what the industry might need, you know, from those young, young folks or don't have to be young. You know, wherever you are in your career, they're there are pivot points. And so that we're very focused on that, you know, especially in the context of professional and executive degrees and executive training.

Daniel Burstein: Well I for one, feel smarter after the hour we spent together with Cicero and Schopenhauer, it’s been very lovely. Michael, thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Michael Diamond: Well, you're too kind Daniel, it's a lot of fun, actually. I really, really enjoyed it. And I'm sorry I have to run, but it's really a wonderful experience.

Daniel Burstein: Totally understand, and thanks to everyone for listening to how I made it marketing podcast. I hope you learned as much as I did.

Get Better Business Results With a Skillfully Applied Customer-first Marketing Strategy

The customer-first approach of MarketingSherpa’s agency services can help you build the most effective strategy to serve customers and improve results, and then implement it across every customer touchpoint.

Get More Info >MECLABS AI

Get headlines, value prop, competitive analysis, and more.

Use the AI for FREE (for now) >Marketer Vs Machine

Marketer Vs Machine: We need to train the marketer to train the machine.

Watch Now >Live, Interactive Event

Join Flint McGlaughlin for Design Your Offer on May 22nd at 1 pm ET. You’ll learn proven strategies that drive real business results.

Get Your Scholarship >Free Marketing Course

Become a Marketer-Philosopher: Create and optimize high-converting webpages (with this free online marketing course)

See Course >Project and Ideas Pitch Template

A free template to help you win approval for your proposed projects and campaigns

Get the Template >Six Quick CTA checklists

These CTA checklists are specifically designed for your team — something practical to hold up against your CTAs to help the time-pressed marketer quickly consider the customer psychology of your “asks” and how you can improve them.

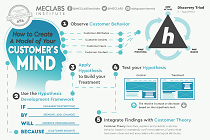

Get the Checklists >Infographic: How to Create a Model of Your Customer’s Mind

You need a repeatable methodology focused on building your organization’s customer wisdom throughout your campaigns and websites. This infographic can get you started.

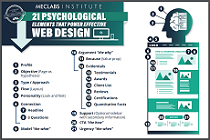

Get the Infographic >Infographic: 21 Psychological Elements that Power Effective Web Design

To build an effective page from scratch, you need to begin with the psychology of your customer. This infographic can get you started.

Get the Infographic >Receive the latest case studies and data on email, lead gen, and social media along with MarketingSherpa updates and promotions.